“Bycatch” – An Artistic Homage to the Throwaways

Shame-faced Crab illustration by Maria Johnson.

The sound of waves lapping on the side of a fishing boat sonically greets you when entering the Hanson Gallery at The University of Arizona Museum of Art. It emanates from a small computer speaker in the corner, subtly broadcasting the audio associated with the 14-foot-wide, 10-foot-tall video projection on the room’s east wall.

As you turn to watch the video projection, your eyes pause to take in the bar table in the middle of the room. Maybe you salivate a bit when you see the faux shrimp cocktail presentation adorning the table, complete with white wine glasses, red napkins and poetic menus. Maybe you imagine yourself sitting on one of those black bar stools and squeezing lemon on the tasty crustacean before dipping it into cocktail sauce and popping it into your mouth, slowly savoring the meaty delicacy. But your eyes are pulled to the east wall, to watch the projection of what takes place in order to bring this delightfully delicious arthropod to our collective plates and our – seemingly insatiable – palates.

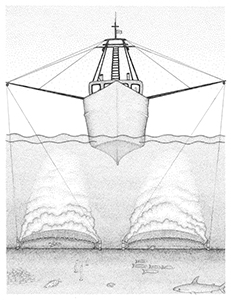

The 11-minute video is a montage of excerpts filmed on a Gulf of California shrimp trawler, a vessel that drags several nets along the sea floor to capture brown shrimp during the night when the shrimp are bedded down in the aquatic bottom, scientifically known as the benthic zone. The projection brings powerful moving imagery to the gallery’s multimedia “Bycatch” exhibit that features gorgeously detailed ink on Bristol paper illustrations by Maria Johnson, a marine conservationist and Prescott College adjunct professor. Accompanying her work is poignant poetry by Eric Magrane, who is both a PhD candidate in UA’s School of Geography and Development and a research associate with UA’s Institute of the Environment.

Trawler illustraion by Maria Johnson.

Johnson’s visual art and Magrane’s poetry pay homage to the sea creatures considered basura (trash) by the fisheries. Organisms such as crabs, turtles, eels, sting rays, sea horses and numerous fish species are the incidental casualties – comprising over 80% of what is caught in the nets – shoveled overboard to waiting sea lions and pelicans once the shrimp are sorted out from the writhing mass of beings dropped from the nets onto the boat decks.

The complement of illustrations, poetry and video draw you into a world of sea life, and sea death. It showcases the hidden actors, the bycatch, in this larger international economic drama. A drama that Johnson and Magrane were invited to document and catalogue as scientific observers on a Mexican fishing vessel through Prescott College’s Kino Bay Center for Cultural and Ecological Studies program.

In conversation with Johnson and Magrane, the two talk about the countless intricacies associated with the Gulf of California’s shrimp trawling industry. “As a geographer, I think about the multiple ways of trying to make some sense of what’s happening on the boat, because there is that process of being knee-deep in the fish, but then there’s global economic processes that are embodied in this interaction that is happening,” Magrane conveys. “It’s a way for humans to make a living. Although, most, if not all, of the people that work on the boats do not own the boats. There’s an effect that this has on the local and smaller scale fisher people of the region and the indigenous communities of the region, so it gets very complicated very quickly.”

As American consumers removed from the region’s fiscal realities, it may be easy enough to decide to stop consuming shrimp, to not be a part of this extractive industry and wonder how people can choose to earn their living by participating in disruptive ecological devastation. But the fact is, people are going to – understandably – do what they need to do to feed their families.

“The communities around the Gulf of California are so heavily focused on fishing, whether it’s large scale like trawling or tuna fishing or whether it is small scale,” Johnson explains. “It’s hard to find other (employment) options and fishing is a tradition. Many of the people working on the boats… it’s what their fathers did and it’s the life they have gone into for whatever reason.”

The other reality is the “very significant cultural differences, where different groups of people interact with different animals in different ways. You have some cultures where fish are food and that’s the only food that’s there. And some groups of people keep fish in aquariums. Or, we relate to cows in different ways, we relate to all these different species in different ways on this cultural and individual level,” Johnson elucidates.

Johnson and Magrane speak with compassion when discussing the industry’s players. They have reverence for the people who cast the nets, they feel for the creatures needlessly dying. I wonder how it is to be on the deck, cataloguing the organisms as they suffocate to death.

“You have to leave a part of your compassion in this other place and come back to it later, or at least that’s how I sometimes interact with it because if I’m just purely myself as a feeling and sensitive person on that boat, I just want to throw everything off board and save every little creature and cry, because it is so intense,” Johnson shares. “But you’re there and you have a job to do and you’re with people who do this for a living, and you want to respect that and collect data and have conversations, so I feel myself kind of leaving a part of that onshore and coming back to it.”

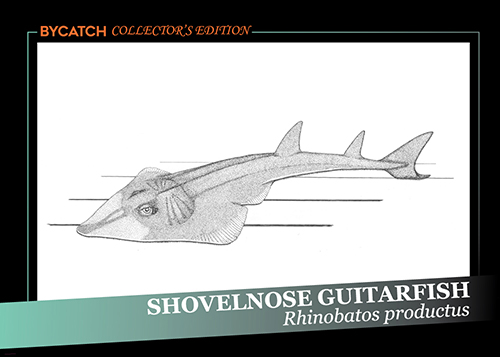

Shovelnose Guitarfish illustration by Maria Johnson.

Courtesy of Maria Johnson

“I think of the role of art and poetry and social science and social theory, in some sense, as being a way to pay witness to what is happening,” Magrane adds. “What going at this project through poetry and art does for me is to try to make some sort of sense, some sort of marking of this relationship that is being played out on the boat.”

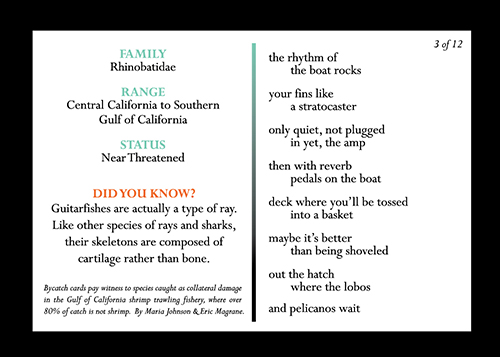

Poem by Eric Magrane.

Courtesy of Maria Johnson

“I know that a lot of what Eric and I have tried to do with this project, as Eric was saying about paying witness to these, not only the species (collectively) but these individuals both through poetry and through illustration, it’s been a really beautiful process. Going back to what I was saying earlier about leaving that compassion at home, this project has been a way for me to come back to that and really physically sit down and spend time with an actual individual (creature) that maybe we encountered in 2015, or that I encountered in 2013, that I actually remember, or that we actually weighed and measured and maybe we have a photo of it or maybe it’s something in our minds, or we remember that feeling of that fish’s slime on our hands or the way that it moved,” Johnson says, regarding their artistic processes. “Then to translate that into illustration and into poetry and honor and respect those individuals and those species, that’s been this very meaningful part of this project to me, that’s given me an opportunity to slow down and look at them as individuals and kind of make room to give that life space again, just in a different way.”

A unique aspect of the exhibit is the 3.5 by 2.5-inch trading cards on display, which are available for $10 in the museum’s store. They include Johnson’s drawings and excerpts of Magrane’s poetry of rolling couplets. (The poetic form, explains Magrane, was inspired by “the experience of being on the boat, the lull, the boat rolling on the water, the movement in that space.”) The idea behind the trading cards was based on Catholic remembrance cards, baseball cards and lotería cards.

“It’s both riffing off of baseball cards or trading cards and the back (of these cards) riffs off it too with the facts about the species along with excerpts from the poems. But the idea of using this form, a collector’s edition for something that is basura, plays against that,” Magrane shares. “Because bycatch, almost by definition, is not valued, it’s the leftover, it’s the waste. So, using the form of the collector’s edition trading cards kind of critiques that in a sense, puts a different play on that, there’s a little bit of cognitive dissonance with that there.”

“Bycatch” grew out of Johnson and Magrane’s involvement with the 6&6 Artists|Scientists project, which is an offshoot of the Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers (N-Gen) interdisciplinary network “of individuals and institutions committed to the rich social and ecological landscape that spans the mainland Sonoran Desert, the Baja California Peninsula, the Gulf of California, and the US-Mexico borderlands,” according to the NextGenSD.com website. Find details on the “Bycatch” project at NextGensd6and6.com.

The exhibit is on display through April 2 at the UA Museum of Art, 1031 N. Olive Rd. Call 520-621-7567 or visit ArtMuseum.arizona.edu for hours and admission prices. Pick up the March/April issue of Edible Baja Arizona to see several “Bycatch” illustrations and poems.

Category: Arts, DOWNTOWN / UNIVERSITY / 4TH AVE