Revisiting Steve Farley’s Broadway Tile Murals, 20 Years On

There’s not much in our city’s history that can be pinned down with a precise date—not the time the first O’odham people settled here, not the week when someone thought it might be nice to build an adobe hut within sight of the Santa Cruz, not the hour when a bureaucrat released the funds to destroy the barrios that lay under what’s now the community center. But it is possible to put a date to the day when, for better or worse, a long-declining, somnolent downtown took the first step toward being reborn: May 1, 1999.

To understand that claim, we need to step back a couple of years before then. Steve Farley, a native of California, was fairly new to Tucson, a transplant from his native Southern California by way of a stint in the Bay Area, where he’d worked for a few years for the weekly San Francisco Bay Guardian and then started his own graphic design business. He wanted to get back to drier, hotter country, but Southern California was expensive and crowded. Enter Tucson, a welcoming community for an artist—and Farley was soon right at home here, doing art photographic and graphic design.

Somewhere along the way, not long after he arrived, opportunity came knocking. Farley and his then-wife, Regina Kelly, were working on a public history project with teenagers on the west side, immersing themselves in local lore. Hearing of the project, a resident, Gilbert Jimenez, came to a meeting with a stack of photo albums dating back half a century. The first image Farley and Kelly saw was of a young, purposeful-looking Jimenez striding along Scott Avenue, a pile of books riding on his right hip, headed toward school. Other photographs followed, taking from an angle low enough that the subjects of the portraits appeared to be superheroes out of a comic book, men, women, and children on their way to meet destiny. Jimenez was one, the future his. The pose was much in the vein of the social realist art of the time, but in the half-century since it had fallen out of fashion—and now here it was, with numerous examples to point to.

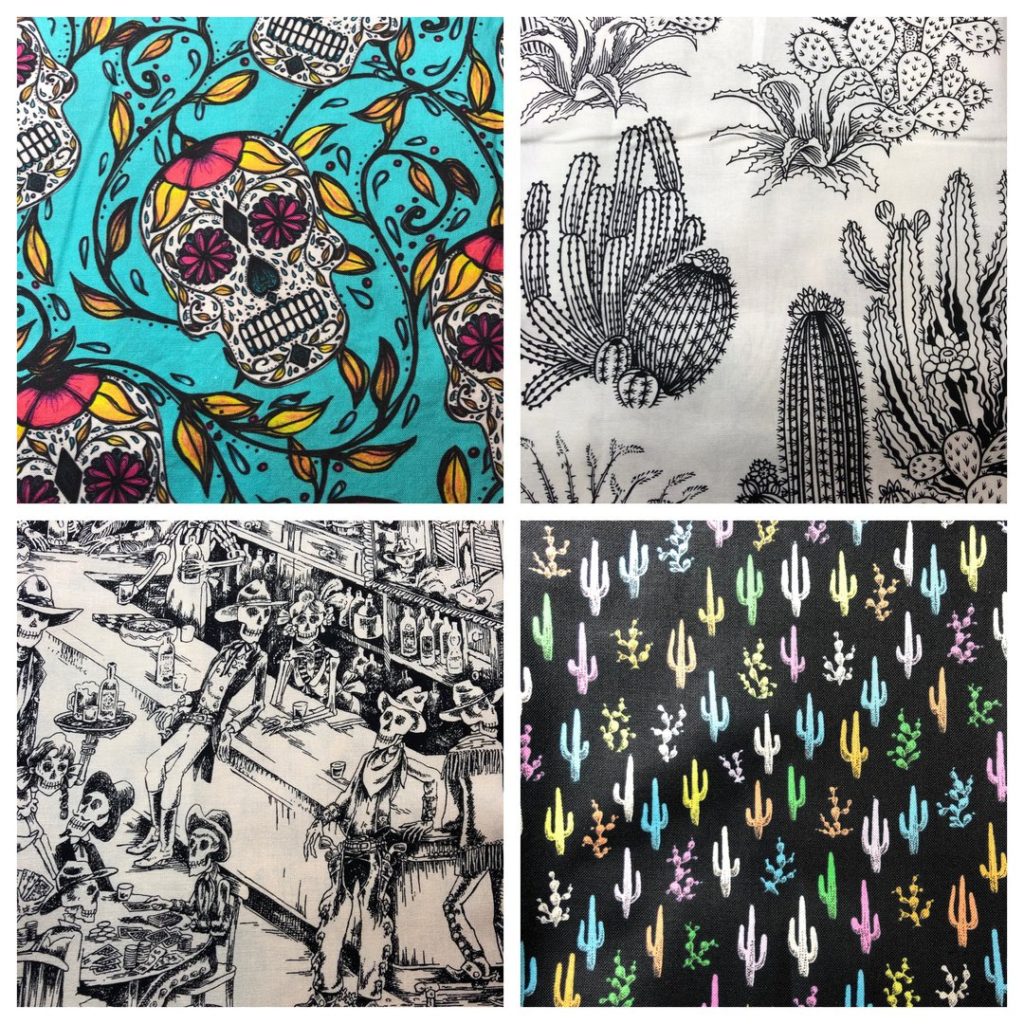

Farley, who about that time had come up with a new process for printing photographs on ceramic tiles, resolved that one day he was going to figure out a way to incorporate those images into some project or another. Opportunity knocked again, just a few weeks later, when a “call to artists” arrived in the mail from the Tucson Pima Arts Council. Four walls, the call announced, were going to be made available for public art at the new terminus of the Aviation Corridor with Broadway at the underpass under the Southern Pacific railroad bridge, the eastern gateway to downtown. Farley’s idea was to use that space to erect a tile mural highlighting the street photography of the sort he had seen in Gilbert Jimenez’s album. He set about writing a proposal detailing that vision and the processes he would use to print the photographs, a process he calls “more biological than technical.”

“There were a lot of entries,” says downtown art gallery owner Terry Etherton, who was on the advisory board of TPAC at the time. “We narrowed it down to five. I didn’t know who Steve was, only that he was new to town and that he’d never done any public art before. But his proposal was so well grounded in history that it seemed like he’d been here all the time, and it was so well thought through, down to the tiniest detail and the last penny. Really, it was the smartest proposal I’d ever seen, and nothing honored Tucson’s history like his did. I supported the project from the get-go. Twenty years later, I’m glad I did.”

The other judges for the competition were unanimous in agreeing with Etherton, and they awarded Farley $171,000 to complete the project—a sum that sounds comfortable until you calculate the costs of making the art and spread it out over the number of hours required to make that art, at which point Farley might have done better to take a straight job.

He didn’t, but the race was on: From the time he started in earnest until the unveiling wasn’t much more than a year, and in the meanwhile there were photographs to find and tiles to make. The word went out that Farley and Kelly were on the hunt for street images from downtown’s golden age, back when all the city’s barrios were alive and the city center was where you had to come to buy shoes or a soda and see a film. Images began to turn up. One photo of an impossibly thin, impeccably dressed young man, a young god whose shoes gleamed whiter than the sun, turned out to be beloved musician Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero. He joined in the cause, performing at a benefit concert at which Linda Ronstadt made an appearance. Consciousness raised, the word out, people from all over the community began to turn up with images, and where there had been a desert before there was now a flood.

Meanwhile, Farley, Kelly, and the budding researchers with whom they were working began to find out more about the street photographers themselves, who freelanced for a downtown druggist with a charmingly simple operation: They’d snap a photo of an approaching pedestrian, give that person a card with a number and an address at which to pick up the shot, then develop the film and deliver it. A package of eight prints went for a buck and a quarter. The work was artful, capturing downtowners and visitors in midstride as they went about their day. The ploy worked, too. The photographers took as many as a thousand shots a day of the people whom Farley called “heroes and neighbors,” doing a thriving business until downtown slowly began to board up in the late 1950s and early ’60s, as shops moved to new centers such as El Con and Casas Adobes and the north and east sides exploded.

(Steve Farley at the mural dedication in 1999. Photo by Andrea Smith.)

Anyone who’s listened to Steve Farley make a political pitch in the years since knows that he knows that the devil truly is in the details—and that he’s a detail man par excellence. Finding those street images was a monumental undertaking in itself, one fraught with difficulties, for, as Farley says, “There’s always a risk of putting real people in public art.” No one ever complained, he adds, and as it turned out, it was just as difficult to narrow the number of images down once a mountain of them had been assembled as it had been to find and identify them.

In any event, rounding up all those images involved coordinating the efforts of many people and reaching out to many more, making cold calls, knocking on doors, talking and talking, fundraising, meeting, planning, delivering—in short, doing politics. Farley completed the project on time and under budget, but, as he says, “the bug had bit.” It wasn’t too long before he was running for public office, serving as a state representative and later senator, mounting runs for governor of Arizona and, this year, mayor of Tucson.

Working with longtime partners Rick Young and Tom Galloway, Farley has since gone on to do public art projects in cities all over the country. (See www.tilography.com for more on them.) Fifteen years after the Broadway Underpass mural project, the modern streetcar came onto the scene in Tucson, something that he’d been promoting—and scrapping for in the legislature—for years. That added a whole new layer to the downtown he envisioned as a newcomer, one that, at least in its better manifestations, is the one we have today.

As for the murals themselves, Farley points out that, unlike most available surfaces in this town, they’ve never been seriously vandalized. That might be the luck of the draw, but more likely it’s a sign of the respect that everyone in the community has for the army of ghosts and elders who inhabit those walls. A few tiles have been damaged here and there, and the city hasn’t done much to correct it, about the only downside that Farley finds in the whole project. The city, he says, has long since fallen down on its contractual obligation to maintain the project, a matter of some caulk and a few hundred dollars.

That would be money wisely spent, for the Broadway Underpass mural project is among the best known and most heavily visited sites of public art in the state, framed by Simon Donovan’s striking Rattlesnake Bridge on one side and a growing, constantly evolving downtown on the other. Great-grandchildren come to see their great-grandparents enshrined in tile, standing ten feet tall. Their great-grandparents oblige, looking like demigods—more than ordinary mortals, at least—in their crisp new blue jeans, their Stetsons and fedoras, their nearly pressed wool dresses and brilliant white shirts. Abuelas look at themselves as young girls, old men as boys out for a lark on a hot Saturday afternoon. Developers walk alongside artisans, cotton farmers, and window shoppers, lost and now refound in time. As Farley said in his speech marking the opening of the mural, “we have enough monuments to lizards and ocotillos. We have too few celebrating the everyday Tucsonans who built Tucson.”

Call it May 1, 1999, then, the day when Tucson, with a wall of art 18 feet tall by 158 feet long, took a giant step toward remaking a moribund downtown into the space it is today. “The murals were an intentional way of reminding people that downtown was and can be the heart of the community,” says Farley, 20 years on. “And they honor a past that we should always remember.”

Also find us on...