Nature

Interstate 11: A Road to Nowhere

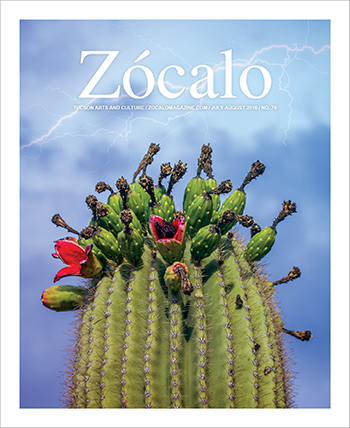

Saguaro National Park West, looking into Avra Valley

Break out a map of the United States. Start at the Canadian border, at the Michigan town of Port Huron. Trace your finger through Flint and Lansing and down to Indianapolis. Arc southwestward through Paducah, Kentucky, to Memphis, then cross the Big Muddy near Greenville, Mississippi, and barrel down to Texarkana, Houston, and on to the Mexican border at Laredo and Brownsville.

You have just described what has been slugged Interstate 69, the so-called NAFTA Highway. It was approved way back when that trade agreement was first signed, with plans costing upwards of $2.5 billion. So far only segments have been built, since the federal government has been slack on infrastructure since the days of the Great Recession, and the current administration hates the very notion of trade agreements in the first place. About the only place where much activity is taking place is Texas, where, for the past decade, sections of the highway have been laid out and others constructed using funds from tolls, public-private partnerships, and fees imposed on commercial vehicles.

Now focus on Arizona. Draw a line from Nogales to just north of Green Valley. Jog to the west through the Avra Valley behind the Tucson Mountains. Follow a line roughly parallel to the existing Interstate 10 up to Casa Grande, then jog west again through the Maricopa Mountains to Buckeye. Go west more, across the wetlands of the Gila and Hassayampa Rivers, and follow Aguila Road and the Vulture Mine Road up to Wickenburg.

You have just described the southern reach of what has been designated Interstate 11, following US transportation conventions that number north-south highways sequentially from west to east and east-west highways from south to north. Like I–69, its ghostly counterpart, I–11 is meant to hasten the flow of goods from Mexico north to Canada and vice versa, connecting to roads leading to lucrative markets in Salt Lake City, Denver, the Bay Area, Seattle, and so forth.

Like I–69, portions of I–11 already exist in the form of a US 93 that runs north from Wickenburg to Kingman and thence to Las Vegas over the recently built Mike O’Callaghan–Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge at Boulder Dam. Beyond Las Vegas 93 has been improved only here and there, but planners at the Arizona Department of Transportation are itching to get going, Texas-style, without waiting for the rest of the Mountain West to catch up.

Now, highways are like water: as the old saying goes, water flows uphill toward money, and roads flow either to where money exists or where it can be made—one reason why, when Loop 202 was slated to be extended around the South Mountains of Phoenix, there was a quiet scramble to buy up the land where the road would be built. If you care to go up and have a look at that massive construction project, which is supposed to be finished by the end of this year, you’ll see another fact about highways: Though the roads themselves are comparatively narrow, they require huge tracts of land on either side of them to be bladed, cleared of vegetation, and leveled.

ADOT’s preferred route, across great stretches of undeveloped land, would visit destruction on scores of thousands of acres of prime Sonoran Desert land. Much of the Tucson stretch lies adjacent to Saguaro National Park and Tucson Mountain Parks. Although the plan overlooks the fact, I–11 would also isolate Ironwood Forest National Monument, which at least some members of the Trump Department of Interior have made efforts to decommission, the better to privatize it and make some of that longed-for money.

Says Kevin Dahl of the National Parks Conservation Association and a longtime environmental activist, “Improving I–19 and I–10 through Tucson would be so much more beneficial to our community’s transportation needs than a new freeway in a location and direction that almost no one in Pima County needs to travel. Add the facts that the new freeway has huge impacts and a huge cost, and we really do have to ask why this alternative has not been fully explored and reviewed. We and others who have been involved in scoping and stakeholder process have wondered why the emphasis on developing the problematic Avra Valley route.”

ADOT counters that it is offering alternatives, but it also makes plain that the route I asked you to trace from Nogales to Wickenburg is its preferred one, its first choice, the course it wants Arizonans to embrace, writing the collateral damage off as a cost of the progress that feeds The Machine. Some of its arguments seem to be stretches: for one thing, ADOT says, I–11 will have a “homeland security” dimension in the event that the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station at Wintersburg, which the new road will pass close to, blows a stack, allowing for the rapidly developing West Valley of Phoenix to be evacuated. And “rapidly developing” is no exaggeration: It’s the fastest-growing part of our fast-growing state. Small wonder that Bill Gates, the former Microsoft head who once was reckoned to be the richest man in the world, bought up a 20,000-acre tract of land between the White Tank and Belmont Mountains for a reported $80 million. The location, as it happens, is right in the path of the proposed interstate, assuring the likelihood of a handsome return on the investment.

Why build a new interstate that will destroy prime desert land, disrupt wildlife corridors, churn up public domain holdings, turn national parks and monuments into islands, and effectively bypass existing cities and their infrastructure in favor of seeding new ones in a state already strapped for water in the face of a quickly changing climate? Why, money, of course: Money for agricultural interests, trucking companies, landowners, developers, roadbuilders, all the usual suspects. Money for unseen future interests as well—perhaps for the Spanish conglomerate, for instance, that has turned the Indiana segment of Interstate 80, which American taxpayers paid for years ago, into a private toll road that generates billions of dollars annually. Doubtless such a concern is waiting in the wings, for, as former Bush administration US Secretary of Transportation Mary Peters notes, “While per-gallon fuel taxes served as a proxy for our highway needs in the past, the pending insolvency of the federal Highway Trust Fund proves that model to be unsustainable.” Funding new highways, in other words, will come from other sources—including the possibility of mileage taxes, private ownership, tolls, and the like.

Meanwhile, building I–11 along the route that ADOT’s planners hope for will cost untold billions of dollars—and at least $3.4 billion over improving existing highways in Tucson alone. Tucson civic leaders have voiced opposition to the new road precisely for the reason that the money would be better spent locally rather than bypass the city altogether. It would certainly be possible to use existing roads, though it would be messy: Just look at I–10 around Houston, parts of which in west of downtown run eleven lanes wide, and anyone who has to travel the interstate in town or between Tucson and Phoenix will probably not be enthusiastic at the prospect of yet more traffic filling an ocean of asphalt. Almost as if a threat as much as a scenario, some ADOT planners have even advanced the notion of a stacked I–10 through Tucson, the upper deck headed north and the lower deck headed south, which seems to offer a little slice of hell for future motorists.

That future is very much of concern, for unless vast pots of money magically appear, it may take ten or twenty years for a 268-mile-long new highway to be completed. A lot can happen in that time, including the possibility of driverless vehicles that can efficiently use existing roads—or the development of newer and better forms of transportation, such as high-speed trains, that can deliver goods transcontinentally in far less time than any semi could. The age of the highway and of the automobile may well be drawing to an end, should be drawing to an end, though there are powerful forces at work seeking to extract every last cent possible from a fossil-fuel-based economy and opposed to anything that looks progressive, renewable, or “soft.” One of the last big highway bills was passed under the Obama administration, and even there the president slated $8 billion for the development of high-speed intercity freight and passenger railroads. Retrograde in every respect, the Obama administration’s successors have been busy undoing that, of course.

How do you and I benefit from a road that will speed up the transport of winter vegetables from Mexico to Canada? How does Arizona benefit from a diminished, fragmented desert ecosystem? It doesn’t, and unless you’re a mogul in the making, you and I don’t. But those powerful interests are at work, and landowners and developers, especially in the Phoenix area, are already counting their money as the Valley continues its inexorable sprawl, now to the west.

This is a road to nowhere, and it should be opposed. The Arizona Department of Transportation is accepting comments from the public until July 8, and we urge all those who care about the health of the Sonoran Desert to urge ADOT to find other alternatives—whether following existing roads or scrapping the project altogether. Comments—a simple “no” will do—can be sent online at www.i11study.com/Arizona, delivered by voice at (844) 544–8049, or sent by mail to I–11 Tier 1 EIS Study Team, c/o ADOT Communications, 1655 W. Jackson Street Mail Drop 126F, Phoenix, AZ 85007.

The Mesquite Harvest

Screwbean, velvet, and honey mesquites pods. Photo by Brad Landcaster

It’s So Much More Than Just Milling Flour

It’s summer time again and, as many of you already know, that means it’s also mesquite harvesting and milling season in Tucson. And where including mesquite flour in your diet is a great way to add some diversity of flavor to your favorite culinary staples, Desert Harvesters Co-Founder Brad Lancaster would like you to know that the production and cultivation of native wild foods here in Tucson goes much, much further than simply whetting the appetites of local foodies. “We’re trying to get everyone to see the whole picture,” says Lancaster, “so the harvest is way more than just the pods.”

Our current agricultural system, says Lancaster, is based on “using imported plants, imported water, and imported fertilizer,” all of which, he points out, takes a major toll on our environment. But the plants that are native to the Tucson area—and that sustained life here for thousands of years before we were tapping the Colorado River as our primary water source—require no such interventions. The native wild food producing plants like the mesquite and ironwood trees, and the cholla and saguaro cacti, he says “are plants that can not only survive here, but thrive here with no imported water or fertilizer.” That’s why Lancaster says that Desert Harvesters is “looking at how we can use what we already have for free in a way that doesn’t deplete the ground water, doesn’t deplete the surface water…but reinfuses our ground water and reinfuses our rivers with water while reducing flooding.” And, Lancaster says, planting native wild food plants “where we live, work, and play,” while incorporating what he calls “water harvesting earthworks” helps to do all of these things while simultaneously improving our city’s landscape, as well as the habitat for local wildlife.

For this reason, though he says that local landscapes are currently dominated by non-native mesquite species that were largely selected for their tendency to grow quickly, Desert Harvesters focuses its efforts on the three types of mesquite tress native to the region—the screwbean, velvet, and honey mesquites. Not only are the local trees more consistent in taste and texture than imported varieties, but Lancaster says that they are also more beneficial to a number of native birds and insects. He says that a native mesquite will attract over sixty different native pollinators, whereas a non-native tree only attracts about a dozen. Thus, birds like the Wilson’s warbler have adjusted their migration patterns to coincide with the blooming cycles of native mesquites, and have therefore come to depend on those cycles in order to fatten up before the annual trip to their summer range about two-thousand miles north.

In support of their mission to increase the abundance of native wild food plants growing in and around Tucson, Lancaster says that Desert Harvesters is planning at least one seed-gathering expedition to look for native mesquites that taste great, ripen pre-monsoon (to avoid the growth of toxic, invisible molds that begin after the rains), and produce dense pod clusters for ease of harvesting. The group intends to harvest the seeds of these tress to sell at their events. That way, interested parties can be sure that they are planting native trees that not only provide summer shade and excellent wildlife viewing opportunities year-round, but will also provide them with a few pounds of naturally sweet, gluten-free flour every summer to utilize as they see fit. Lancaster says that some of his favorite uses for mesquite include making crackers, pie crust, and pizza dough, or using it to mix with or make coffee. He says it can also be cooked down and made into a syrupy sweetener that actually slows the body’s intake of sugar, making mesquite an ideal food for people who suffer from hypoglycemia or diabetes.

Lancaster says that mesquite beans produce a wide range of flavors, from “sweet, to nutty, to sweet-and-sour, to kind of lemony,” and that each and every tree is unique in its flavor profile. Thus, he says it’s important to sample from a number of trees when trying to find your prefect pod for harvest. He says that, when sampling from a mesquite, you should be sure to actually pick from the tree and not from the ground, and that “the pod should be dry enough that, when you bend it, it immediately snaps in two.” It should also be completely yellow, without any green left on it. You can gently work the bean with your teeth and tongue to extract the flavor when sampling, then spit it out. But be careful, as Lancaster says that the seeds are hard enough to crack a tooth. The hammer mills they use to turn the pods into flour, however, are strong enough to grind those seeds right along with the rest of the pod. When sampling mesquite beans, Lancaster says that you will not only want to taste for the presence of any one of the four “bad flavors,” which are “bitter, burning, chalky, or drying of the mouth or throat,” but that you should also look for beans that are particularly good-tasting to you. And it’s not enough to decide simply based on the initial flavor experience, says Lancaster, but that you should also wait for the aftertaste before making a final judgment. “It doesn’t matter how good of a cook you are,” he says, “you can’t take a bad flavor out of a bad-tasting pod.”

The mesquite-harvesting events this season kicked off with a fundraiser at La Cocina on May 31 which featured live music, along with food and drinks made from local wild ingredients, and they will continue throughout the month of June. For those looking to learn how to harvest native wild foods for themselves, Desert Harvesters will hold guided native food-harvesting walking and biking tours beginning at the Santa Cruz River Farmers’ Market at Mercado San Augustin on June 16 (tickets are $10). A concurrent demonstration at the market will showcase ways to turn those harvested ingredients into a range of culinary delights. The following week at the same location, June 23 is the 14th Annual Mesquite Milling and Wild Foods Fiesta, to which you can bring your clean and sorted mesquite pods to be ground into flour on site for a small fee. For reference, Lancaster says that it takes about five minutes to grind five gallons of harvested pods into about one gallon of flour. Other events include a mesquite seed collecting workshop, a happy hour fundraiser at Tap & Bottle, and a saguaro fruit harvesting workshop. More details are available on the Desert Harvesters website, the address to which is provided below.

Though Lancaster doesn’t expect to turn all Tucsonans into expert harvesters of wild food overnight, he says that the work of Desert Harvesters serves the greater purpose of “trying to shift how people see agriculture, and to (encourage them to) practice it in a way that does not degrade our environment, but enhances it.” For this reason, the Desert Harvesters events are “meant to be a full hands-on, mouth-on experience; we want people to not just get the theory, but to actually experience it,” Lancaster says. This kind of immersion, he says, is the only way to fully grasp the connection that already exists between the people that live in Tucson and the historic, natural agriculture of the region they call home. “We’re trying to deepen people’s engagement and relationships with these plants,” says Lancaster. And once you begin to harvest from the abundance that occurs naturally around you, Lancaster says you’ll likely find that, not only is it better for you, and better for the environment, but it’s ultimately “easier than going to the store.” And cheaper, too. What could be better than that?

For more information on the Desert Harvesters-sponsored mesquite milling and wild food harvesting events taking place this month, visit them online at DesertHarvesters.org.

Bennuval!

Dante Lauretta, UA professor of Planetary Science & Cosmochemistry & Principal Investigator on NASA’s OSIRIS-REx Mission

Celebrate an Asteroid that Might Collide with Earth

Hurtling through space at 62,120 mph is a rather large rock. It’s 500 meters—or about one-third of a mile—in diameter, and even though that’s on the small-to-medium range as far as asteroids are concerned, it’s one that University of Arizona Professor of Planetary Sciences Dante Lauretta has his eye on. Partly because there’s a decent chance that it will one day collide with the earth.

Congress has mandated that NASA identify and monitor all of the celestial bodies over one kilometer in diameter that could eventually present a problem for our planet—those are the ones big enough to wipe out an entire city, or worse. Lauretta, though, thinks that we should be looking for anything larger than fifteen meters.

For reference, the impact on the Yucatan Peninsula that took out all the dinosaurs was about 10 kilometers in diameter; the asteroid that exploded in air over Chelyabinsk, Russia in February of 2013 was only about 14 meters in diameter. Still, Lauretta says that the resulting kaboom from the Chelyabinsk event was equivalent to a roughly 400 kiloton explosion; enough to knock down buildings, shatter windows, and injure a whole lot of people in the city below—the bomb the United States government dropped on Hiroshima in 1945 was closer to 15 kilotons. And, should that 500-meter rock named 101955 Bennu, find its way through our atmosphere, that explosion would be somewhere on the order of 3,000 megatons (emphasis on the ‘mega’).

When Bennu was discovered in 1999, it was about twice as far away from earth as we are from our own moon—that’s pretty close in astronomical terms. And, though you probably didn’t know it, our home planet has a similar cosmic close-call with this particular asteroid about once every six years. But, says Lauretta, in exactly 120 years, Bennu will come so close to earth that it will actually pass between the earth and the moon. And here’s the scary part—after that sub-lunar flyby, there is about a 1/2700 chance that Bennu’s orbit will bring it right back around to earth another forty years or so later; that’s about the same chance you have of dying from a fall down the stairs. Says Lauretta, “You’d probably cross the street with those odds,” but when it comes to asteroids that could wipe out huge swaths of humanity, it’s probably best not to roll the dice.

Lauretta, who is also the Principal Investigator on the University of Arizona’s NASA-funded OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission—a mission that intends to make actual contact with Bennu and return with a piece of it—is hoping that the data he’s collected for the project proposal (an effort that was seven years, five drafts, and a few thousand pages in the making), as well as whatever he learns from the sampling process will prove to be valuable to those scientists about 150 years from now, who will no doubt be looking into Bennu again, perhaps even more closely than Lauretta himself.

Where he is open to talking about Bennu’s potential for impact, Lauretta’s real interest in the asteroid is in the rocks, themselves. Well, not so much the rocks, but what he might find on them. “When we study asteroids,” Lauretta says, “we’re studying the geological remnants from the very beginning of our solar system. So,” he explains, “we’re looking at the processes that led to the formation of the planet earth and to the origin of life itself.” That’s right—Lauretta thinks that those rocks might contain evidence of extraterrestrial life.

Essentially, Lauretta says that there is a certain type of asteroid called a ‘carbonaceous’ asteroid “which seems to have a lot of organic material on it.” By organic material, he mean things like amino and nucleic acids, which he says are the “precursors to important biomolecules” like proteins, DNA, and RNA; what Lauretta calls “the seeds of life.” Bennu is one such asteroid.

The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft is currently being assembled by partners at Lockheed Martin in a clean room facility near Denver, Colo. and is scheduled to launch on Sept. 3, 2016. The spacecraft will then travel for two years en route to the asteroid before flying alongside it for a period of about ten months to “survey and map” the surface of Bennu before they pick an extraction site. The sample collection will be accomplished using a sort-of mechanical-vacuum-arm device that will touch the surface of the asteroid for about five seconds without ever actually landing on it, and then turn around to begin its two-year return cruise.

Lauretta says that this “touch-and-go” method of sample collection is unique to the OSIRIS-REx project. The only previous attempt to collect a sample from an asteroid in space was the partially-successful Japanese project, Hayabusa. After the craft and its collection mechanisms were damaged in a fall, Hayabusa returned to earth with only the particulates that got caught in the machinery as it tumbled over the surface of its target. Coincidently, Lauretta says that Hayabusa II, which launched in Dec. of last year, is expecting to make contact with its own target asteroid within months of when OSIRIS-REx plans to begin their own survey phase. And, since both teams “share the same science goals,” Lauretta says that they have agreed to perform an asteroid sample swap in which each team will get a sample of the other’s rock, if successful. “That way,” he explains, “if either mission is successful, both teams get asteroid sample for their laboratories.” Call it scientific insurance.

Since Professor Lauretta has been entrusted with about $1 billion in federal tax monies for his project, he says he feels “obligated” to engage the community and educate them about OSIRIS-REx. Plus, he’s just really excited about it, and he thinks the rest of Tucson could be, too. “We want Tucson to think of OSIRIS-REx as sort-of the ‘Hometown Kid’,” says Lauretta, pointing out that the spacecraft’s journey is itself a classic treasure-quest story.

In that spirit of education and engagement, Lauretta and the OSIRIS-REx team are hosting an event at the Fox Theatre this month which they hope will serve as the community introduction they’ve been waiting for. Bennuval!, billed as “An Evening of Space, Art, and Music,” will feature music by ChamberLab, performances by Flam Chen and the Tucson Improve Movement, and an “Art of Planetary Science” exhibition. The event will be hosted by Geoff Notkin, former star of the Science Channel series Meteorite Men and owner of the local meteorite collection and distribution company, Aerolite Meteorites, LLC.

Lauretta says that, though people often think of the arts and sciences as at odds, “they’re really complementary”. Artists, musicians, acrobats, comedians, and scientists “are all working toward the same celebration of the human experience,” says Lauretta. And as such, you can expect the Bennuval! show to offer a few surprises. “I don’t want it to be a stovepipe show,” he says. At a recent performers’ meeting, Lauretta told the cast he wanted them to “get on stage with each other and just see what happens.” He then went on to say that he thought “something really interesting and exciting is going to come out of that,” and I wasn’t sure anymore if he was talking about the spacecraft or the upcoming show. Really, he’s probably right on both counts.

Bennuval! takes place on Sat. Sept. 12 at 7pm at the Fox Theatre; tickets start at $18. More information and tickets are available at FoxTucsonTheatre.com. More info on the OSIRIS-REx mission can be found online at

AsteroidMission.org

Also find us on...